Our website was created to help the family members of those who died and participated in Exercise Tiger. Dean Small, son of the late Ken Small, continues with his father's legacy. We are endorsed by the survivors and the families.

Douglas Harlander Survivor Story - LST 531

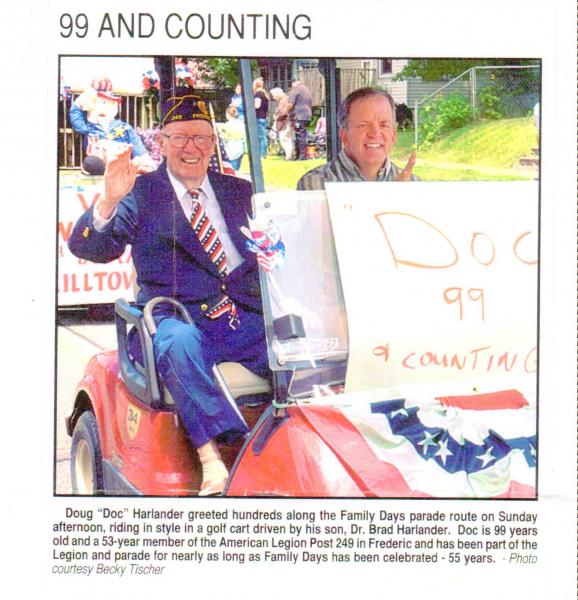

ENSIGN DOUGLAS HARLANDER

Navigation Officer on board LST 531

Resides in Frederic, Wisconsin

Deceased April 29, 2022

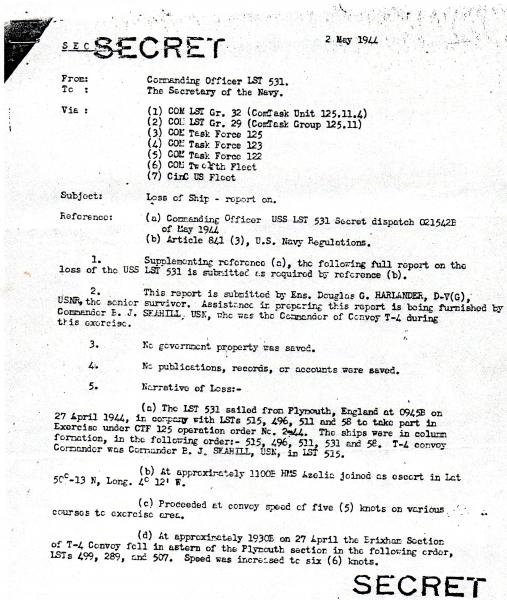

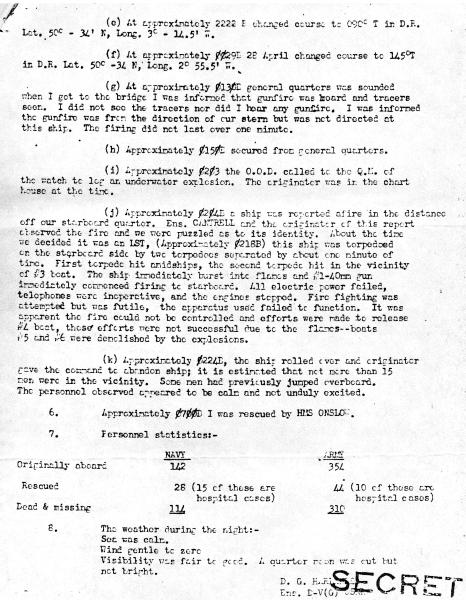

As a surviving officer on board my ship, LST 531, I was assigned to write what had happened on the fateful early morning of April 28, 1944, when two torpedoes from a German E-Boat slammed into the hull of our ship. When the attack happened, my ship was in the middle of a convoy of eight LSTs and on its way to join a mock invasion exercise being held on a stretch of English shore, called Slapton Sands.

On the morning of April 27, 1944, as the convoy left naval headquarters at Plymouth and headed through the English Channel, the destroyer which had been assigned to protect the convoy was commanded into port for repairs. It never joined the convoy and no replacement was sent. Instead the ships were led by a small, British trawler. The convoy left at 9:45 a.m. and picked up three more LSTs on its way. LST 531 was loaded with 354 Army personnel and 142 Navy crew members. The men aboard the ships knew they were on some sort of dry run for the D-Day invasion, but many of the men thought they were embarked on an actual invasion of France because of the sight of the tank decks of the LSTs loaded with trucks, vehicles and tanks. The convoy had traveled all day and into the night. It was early the next morning, April 28th, when the last LST in the convoy, 507, got hit by a torpedo at 0203 a.m. from one of the German E-boats which had snuck up on the two-mile long convoy of LSTs. I remember being on the navigation deck of the ship when the radar man pointed out a “little peep” on the corner of the radar screen. I went out to take a look and was standing on the starboard wing when the first torpedo hit. It felt like a sledgehammer on my feet. It threw me back eight or nine feet. The direct to LST 531 came 15 minutes after the assault on LST 507, and struck the ship’s mid section and engine room, shutting everything down. We were dead in the water. We were completely loaded with trucks, vehicles, tanks, and all of them were loaded with fuel to the hilt. As a result, when the torpedoes went off, it was an immediate mass ball of fire all over the main deck and all over the tank deck. A minute later we were hit again with another torpedo. That one really ripped our seams open. The ship started listing right away and started turning over to its starboard side. It would only stay afloat for another six minutes. Attempts were made to put the flames out, but it was impossible with all the gasoline fueling the fire. The four landing craft, used to transport the troops to the beach, couldn’t be used because of damage and shortness of time, because they were tightly secured to the ship. I followed emergency procedure and went down to the ship’s war room, but no one was there. I went to my own quarters and roused an Army officer and got him a life jacket. I then began evacuating other men in that part of the ship. I realized that saving the ship was futile, so I turned my attention to trying to save men, grabbing life jackets and passing them out. I helped 15 men over the side and I was the last man over the port side. As I crawled over the side, the ship was sinking fast and turning over. By the time I got down to the water line, it had turned over completely and the water was up to my ankles. As I was walking on the outside of the ship’s hull while it sank beneath me, I dove off and got away as fast as I could to avoid being dragged under by the suction of the ship’s descent.

As I swam away from the ship, I noticed a small life raft that had managed to be launched about 20 yards away, being clung to by survivors. Two men lay in the middle of the raft and 15 others hung on the outside of the raft, their legs in the water. The big problem was the water was 44 degrees…mighty cold. The first half hour the water felt cold but after that your arms and legs just got numb and you couldn’t feel the water. You couldn’t hang on to anything either. As the night progressed, there were fewer people around. They slipped away as they became unconscious. Along about six o’clock in the morning you even wished you could be picked up by the Germans, because the men were falling off like flies. We were rescued around 7 a.m. by the HMS Onslow. Our clothing was soaked in fuel and we were hoisted on board the Onslow where we were given a change of clothes and our wounds treated. I was given a cup of tea, but I was shaking so badly I spilled half of it. It was the best drink I’ve ever had in my life!

Survivors were taken to shore where I recall eight or nine ambulances waiting for us. I remember the dock workers who stopped what they were doing to watch intently as we came off the ship on our way to an Army hospital five miles inland near Portland, England. I suppose they thought the whole D-Day thing had started. I suffered from burns but was able to walk to the waiting ambulances.

In the coming weeks I came to realize that the ordeal I survived was not to be officially acknowledged by the Navy or the United States or British governments. I was not allowed to keep a copy of the report I filed about the incident. I feel that the report was classified to prevent damaging the morale of the D-Day soldiers who had to travel through those same waters to reach their destination on June 6, 1944. The sad part of the whole thing is that the surviving family members didn’t know for so many years what had happened to those missing. They were told only that they were missing in action or killed in action. I estimate that at least two-thirds of those on board never made it off the ship and today their remains rest at the bottom of the English Channel.

PERSONNEL STATISTICS:

| LST 531 | U.S. NAVY | U.S. ARMY | TOTAL |

| Aboard | 142 | 354 | = 496 |

| Rescued | 28 | 44 | = 72 |

| Died | 114 | 310 | = 324 |

(15 Hospitalized) U. S. Navy (10 Hospitalized) U. S. Army

SEE ENSIGN HARLANDER'S OFFICIAL REPORT TO THE SECRETARY OF THE NAVY BELOW PHOTOGRAPH

|

| LST 531 being Launched at Missouri Bridge & Iron Works in Evansville, Indiana |

Dr. Douglas Harlander turned 100 years old on February 2, 2020.

He passed away on April 29, 2022, one day after the 78th anniversary

of Exercise Tiger at 102 years old.